Mother tongue: the key to identity, education and a better future

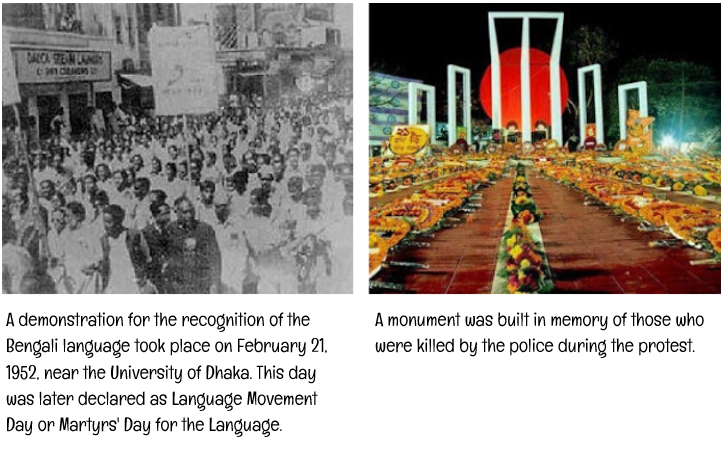

At the suggestion of Bangladesh, UNESCO proclaimed 21 February as International Mother Language Day in 1999. This day, celebrated in Bangladesh as Language Movement Day, is a reminder that language is not only the basis of national identity and a means of communication, but also the key to education - and a way out of poverty.

The BanglaKids programme helps children from the poorest families in Bangladesh to access quality education in their mother tongue. This gives them a chance for a better future. Linguistic diversity is part of humanity's cultural heritage, yet half of the world's 5,000 to 7,000 languages are threatened with extinction.

Bengali

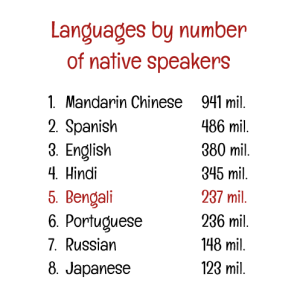

Bengali is the mother tongue of over 237 million people. This makes Bengali the 5th most spoken language in the world. Bengali is spoken in Bangladesh and the eastern parts of India, but it is also found in diasporas in the United Kingdom, the United States and the Middle East. Bengali is the official language of Bangladesh, where it is the mother tongue of 98% of the population, and of three Indian Union states.

Bengali belongs to the Indo-European language family, like Czech, English or Spanish. Bengali is closer to Czech than to Finno-Ugric languages such as Hungarian or Finnish. Bengali is the easternmost member of the large Indo-European language family, with 1.5 billion speakers.

Bengal Renaissance

Bengali is derived from Sanskrit, one of the oldest Indo-European languages, which can be traced back to the 2nd millennium BC. The earliest literary monuments written in dialects of Bengali date from the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennium AD. These were Buddhist and Hindu mystical and poetic texts. However, the language of the high culture of Buddhism and Hinduism was Sanskrit, and in the case of Islamic high culture in the Indian subcontinent, Persian. For a long time, therefore, Bengali was primarily a vernacular language used in people's everyday lives, but it did not produce more complex literary or religious texts. Similarly, until the 19th century, Czech was primarily a vernacular language, overshadowed in high culture by Latin and German.

Bengali as a language of high culture began to emerge only in the 19th century, during the so-called Bengal Renaissance. The Bengal Renaissance refers to a major cultural and intellectual movement of pan-Indian significance, one of the most prolific and distinctive movements of its kind in all of Asia. The Bengal Renaissance included writers and intellectuals who sought to promote the Bengali language, Bengali culture, and social, religious and political reform.

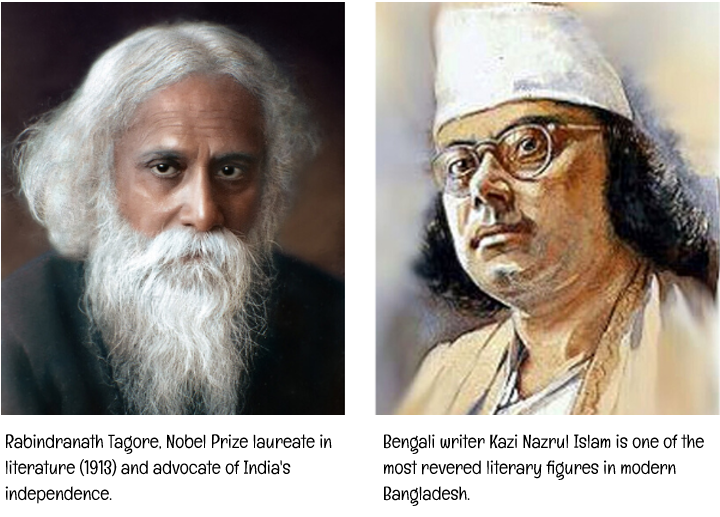

In a broader sense, these writers were also trying to come to terms with the growing Western influences that had settled in Bengal and India along with the British colonisers and their own cultural roots. Some intellectuals wanted to Europeanise as much as possible and saw local traditions more as a hindrance. Others, on the other hand, wanted to define themselves against the West as a civilisational entity in their own right, drawing primarily on their own Hindu or Islamic sources. A third trend attempted a creative syncretism that would overcome both the uncritical adoption of everything Western and the unviable enclosure within one's own tradition. This middle position was held by the most prominent writer of the Bengali Renaissance, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, becoming the first Asian Nobel laureate.

Divided Bengal

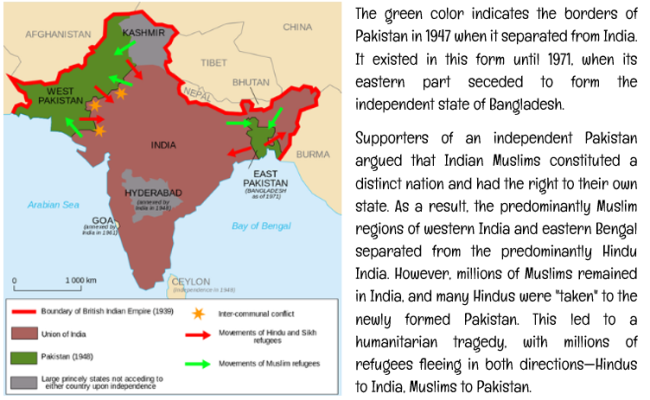

The Bengal Renaissance, like Bengali culture, is a phenomenon that extends beyond the territory of present-day Bangladesh. From the late 18th century until 1947, the whole of Bengal was part of British-ruled India. The division between Bangladeshi and Indian Bengal as we know it did not exist until 1947, when the territory of present-day Bangladesh broke away from India as part of the newly formed Pakistan. At the same time, developments in Bengal were by then closely linked to events in the whole of India, and Bengali writers themselves tended to think in all-India terms.

In today's predominantly Muslim Bangladesh, the cultural mainstream selects mainly Muslim authors from among the older Bengali writers and claims them as 'their own'. In contrast, in the predominantly Hindu west of historic Bengal, now in India, Bengali Hindu writers are canonised. While the Bengali Hindu writer Rabindranath Tagore is most revered in India, the Muslim writer, revolutionary poet and fighter against British colonialism Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976) is most revered in Bangladesh.

Bengali Language Movement

In 1947, the whole of Bengal became part of independent India. In the same year, independent Pakistan broke away from India. The predominantly Muslim eastern part of Bengal also became part of Pakistan. West and East Pakistan were united by Islam, but were linguistically, culturally and geographically distinct territories. West and East Pakistan were separated by more than 2000 km of Indian territory. Moreover, the central government in Karachi, West Pakistan, treated the eastern part of the state as its colony in many respects. This was reflected in its reluctance to grant linguistic autonomy to Bengal. Instead of recognising Bengali, which was spoken by more than 50% of the population in the whole of what was then Pakistan, the central government decided to linguistically bind the new state by introducing Urdu as the only official language.

The demand for linguistic equality arose in the late 1940s. Bengali Language Movement, which broadly developed the idea of a distinct Bengali nation defined by a common language (similar to the Czech national identity). The unequal status of the Bengali language and the unequal economic redistribution in favour of the western part of Pakistan led to growing discontent among the general population and a growing Bengali nationalism among intellectuals.

Day of the martyrs of the language

On 21 February 1952, a rally was held in Dhaka to demand equal rights for the Bengali language. The protest was bloodily suppressed by the police and several people died on the spot. The dead became national heroes, and 21 February became a symbol of the struggle for Bengali language equality and the struggle of Bengalis in general for political independence from Pakistan.

Bangladesh finally seceded in 1971, after nine months of bloody conflict, and 21 February officially became Language Movement Day, also known as Fallen Language Fighters Day.

BanglaKids: Language and education as a way out of poverty

Today, the Bengali language is no longer threatened in Bangladesh, but many children still lack access to quality education. Poverty often traps them in a cycle of illiteracy and an uncertain future. The BanglaKids programme enables children from the poorest families to study in their mother tongue.

Education in their mother tongue gives them not only knowledge, but also self-confidence and a chance for a better life. Language is not just a question of national identity - it is the key to education and a way out of poverty.

Sources:

Knotková-Čapková, Blanka. Bangladéš. Praha: Nakladatelství Libri, 2005.

Lewis, David. Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.